Why is it Cold Even When the Sun is Out?

Here’s a little experiment. Take one friend and shine a flashlight directly in their eyes. Then, take another friend, and shine the flashlight in their eyes, but from off to the side, so it’s not shining directly into their eyes, but just sort of glances off their eye region. Which one stays friends with you longer?

Sunlight works in a similar way. In the summer, we get more direct rays from the sun. After months of direct rays, the Earth has warmed up. As a result, the warmest months are the ones following the Summer Solstice (June 21 in the Northern Hemisphere), the day that the sunlight is most direct.

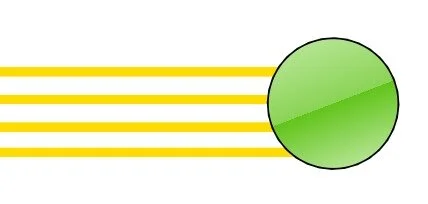

Summer in the Northern Hemisphere. Not drawn to scale.

If you take a look at the picture, you can see that the Northern Hemisphere (top half) of the Earth is tilted towards the Sun and getting more direct rays. The Southern Hemisphere, on the other hand, is getting less direct sunlight. It’s cold down there. (The picture shows June 21, which is the opposite of what the Earth looks like now. Now, the top is tilted away, and we’re getting the indirect rays up North. It’s cold.)

In the winter, the sun’s rays are at more of an angle, so they’re less effective. Since the Earth is tilted away from the Sun, the Earth gets less direct sun, and cools off. The day with the least direct sunlight is the Winter Solstice (December 21 in the Northern Hemisphere) and the coolest months follow shortly after.

That’s also why the sun’s glare seems to be worse in the winter - the sun is lower in the sky, the angle is more significant, and it seems to shine right in our eyes when we are driving. All the darn time.